lēthe

ē is an online magazine by the Noēsis Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy.

By Veronika Zabelle Nayir

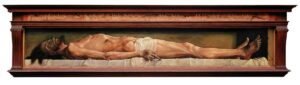

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, 1521, oil on wood, 31 x 200 cm, Kunstmuseum, Basel.

The depiction of a death without transcendence in “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb” by Northern Renaissance painter Hans Holbein the Younger consoles the melancholic viewer by representing and taking seriously the ugly reality of mortality. Holbein’s dead Christ, however, is not a representation of atheism but instead of humanity. With Holbein we see instead of Christly redemption artistic redemption – “the beyond” becomes in this new paradigm the very possibility of art-making in the face of death, a new kind of prayer and consolation and the best place in which we might locate human hope. This paper will read Julia Kristeva’s analysis of Holbein the Younger’s painting in “Mourning and Melancholia” alongside Lullaby a contemporary collection of poetry by Hadara Bar-Nadav, and will attend to the ways in which art and literature might attest to, honour, and transform melancholia.

Holbein’s Christ is a redemptive one because we can only identify with Christ as he is human, in his moments of great suffering (Kristeva 108). This is radically affirming – the realization that even a God is capable of psychological and bodily suffering. We are also compelled, in this act of identification, to be empathetic: the viewer looks upon the dead body of Christ and is totally implicated in his suffering, and also, more significantly, “in his hope of salvation” (Kristeva 134). Thus, Christ’s body, or any other depiction of suffering, acts as a “powerful symbolic device that allows [us] to experience death” (Kristeva 134). Art allows us to anticipate our own deaths, to hope that others might be saved so that we, too, might be. Holbein is not so much depicting a kind of atheism as he is painting the question and struggle of faith. Kristeva addresses this very question: “how could [those who witnessed Jesus’ corpse] possibly have believed […] that this martyr would rise again?” (Kristeva 108). On the idea of “rising” we are brought to Hadara Bar-Nadav’s poetry collection, titled Lullaby (with Exit Sign). Bar-Nadav points here to a goodnight (lullaby) and a goodbye (exit sign) – a hope of waking up again and a simultaneous hope of escape. A lullaby comforts us in darkness, an exit sign shows us the way out. Art, much like faith, does both – it brings to light the question of mortality and offers us a way to navigate it.

Our participation in Holbein’s painting goes further. We notice that Christ is alone in this scene, that there are no mourners around him. This is part of the terror of this depiction – Christ in this representation, unlike in others, is not surrounded by mourners. He is laid in the tomb but also condemned to loneliness. The melancholy of the painting is transformed when we ourselves participate in it – when we are forced to grapple with Christ as his witnesses would, when we are forced to take the place of Christ’s mourners and grieve his human death. Nietzsche writes of a similar idea in The Birth of Tragedy, telling us that artistic representation cannot be understood as mere “pictures on the wall” because “[we] too live and suffer in these scenes” (Nietzsche 23-24). Moreover, Holbein’s work represents a kind of universalism. To be confronted with the thought of mortality is comforting because it is a condition we are all afflicted with, “from the newborn and the lower classes to popes, emperors, bishops, abbots, noblemen, young wife and husband” (Kristeva 118). The danse macabre is a tragedy but a shared one, and it is in this fact that we might find solace.

What, though, is powerful about the sight of a dead God? Why should it console instead of merely disturb? The sight of a dead God is, undoubtedly, a disturbing one. I suggest, however, that what is more powerful as a form of consolation is to see ugliness represented in art – the dead body of Christ is ugly, beaten and bloodied: we are not supposed to imagine or see him in dead scene. Holbein is therefore representing the unrepresentable, that which is mundane and grotesque but what we ought to be confronted with. In order to be consoled, I argue, we must first be confronted with the terrible thing. Holbein therefore practises a sort of brutal realism, and here is where we can locate the humanity of his art. “The artist refused to cast an embellishing gaze”, says Kristeva, hinting at this. (127). The responsibility of writing, too, is to resist lulling (lullabying) us to sleep, to refuse to beautify, to show us truth in all its terror. Kristeva states elsewhere, however, that if one is morose, that “that state can be made beautiful” (122). Here I take issue with Kristeva – it is not that terrible things should be made beautiful in art but instead that we might grapple with terrible things and locate meaning, and therefore beauty, in them. We can beautify by the very act of allowing ugliness to be represented in art and literature. There is therefore a great dignity to be found in the refusal to present things as better than they are. Christ, in Holbein’s painting, is made close to us, close to the truth of things, close to the truth of grief and our own experiences with it – often we are disturbed, despondent, unconvinced of transcendence. We suffer, and so does Christ.

Holbein’s depiction represents the idea that Christ has been forsaken by his own father (Kristeva 110), deserted and abandoned. Just as Christ, the son, is abandoned by God, Hadara Bar-Nadav’s poems, too, deal with the loss of a father (Bar-Nadav 4). Kristeva notes that this severance “is the truth of human psychic life” (Kristeva 136). Disillusionment is therefore a truly universal condition and has a right to expression and depiction. It deserves not to be beautified. Art must capture and reflect the truth of grief if, and before, it is to help us.

We are also invited to wonder about what comes next in Holbein’s Christ scene, invited to hope that death means something more than just dying. The corpse is ultimately just a trace, the thing that remains, and we can wonder about something like the soul. Holbein’s painting shows us a mystery – the in-between of life and death, a purgatorial waiting period, where the watcher/reader holds their breath and hopes. Good writing also addresses (and leaves open, to invitation) these gaps and ambiguities and passageways, and the sensitive reader-witness practices leaps of faith and struggles against nihilism. “Grief is a Mouse”, Bar-Nadav writes, a small mouse “scratching the dark” (59). The dark “presses [this mouse] onward” and eventually “something gives, breaks down…” (59). The grief and courage of the little mouse, who we might take the place of in this dark scene, shows us how we might participate in art and literature: by reading hope into otherwise hopeless scenes, by letting the dark guide us, and by transfiguring something as large and horrible as grief into something as tiny and persistent as a mouse.

What must also be addressed is the significance of Holbein’s depiction of the physical body. Why might the aesthetic privileging of the material body also be consolatory? Holbein presents us with a tortured corpse, stamped with marks of visceral suffering. I think that by representing suffering Holbein in some way legitimises it. Art in this sense can bring the terrible closer to the sublime. It can show the melancholic that the bad and fearsome are worthy of being represented, too. Holbein’s depiction of the body is also a symbolic privileging of the earthly and the human. Our pain, like Christ’s, manifests materially – to bring the body and its suffering to the foreground is to highlight the human condition in all its fragility. To represent wretchedness and the bleak reality of trauma might be gruesome, but also transgressive by expanding our ideas regarding what is representable. Witnessing the defiled body of Christ also shocks us into remembrance – we (or at least I) are unable to forget about the violence his body endured. In Holbein’s painting we bear witness to real flesh – not flesh as metaphor, but flesh in its frailty – blue-green, bloody, bruised flesh. As Bar-Nadav elegizes, “What beauty, what bruise” (Bar-Nadav 1). The bruise is not so much proof of suffering as it is proof of humanity, which is dreadfully beautiful (Kristeva 138).

There might also be a comfort in understanding the human body as organic (Helberg). We see in Holbein’s painting the putrefaction of flesh, and in Bar-Nadav’s poetry she writes of “tissue” and “decay” (Bar-Nadav 16). However, the preservation and embalming of the dead body is what should disturb the reader of Bar-Nadav’s work: “veined with formaldehyde perfume. O, pickle my dead heart […] A chemical permanence blues my eyes” (58). We realise here that decomposition is natural – that there is something beautiful about the body being transformed organically, and not supernaturally – something beautiful about the “green into which you can disappear” (Bar-Nadav 59). Bar-Nadav’s poetry calls to mind the Christian rendering of memento mori: “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Miraculously, Bar-Nadav titles one of her poems “Dust Is The Only Secret” (Bar-Nadav 16).

Kristeva says that Holbein “leads us […] to the threshold of nonmeaning” (Kristeva 135). Bar-Nadav’s parallel line reads “Goodbye meaning in your white coat” (17). We might see, then, the thought of death without transcendence as an existential impasse. The crucial question emerges here: might we still find or make meaning in the face of meaninglessness, when we are severed from the promise that we will be saved through resurrection? For many of us, it is the idea that we might be reborn again that first consoles us, but true consolation might be to cut attachments to these transcendent ideas – to be, in some sense, an iconoclast – to seek transcendence on earth, in humanity and in ourselves. Death is, for the artist-writer, a chasm to be filled – for Bar-Nadav writing is a “strange lullaby […] that sings from its wound” (Bar-Nadav 2). Writing that comforts is the kind of writing that speaks of and from a place of pain – art which keeps melancholy as a painterly or written trace (Kristeva 128). To cast the promise of immortality into doubt is to give mortality new meaning. Here the depiction of death makes death livable and bearable. Death might be meaningless and mortality embodied, but it is this break, this sense of abandonment, that serves as an “indispensable condition for autonomy” (Kristeva 132) – artistic or writerly autonomy especially. This is the first step in seeking out earthly emancipation.

Not only is art a “lullaby […] that sings from its wound” (Bar-Nadav 2), it is the wound of mortality that gives art its distinct voice: we cannot make art without the prospect of death looming over us. To make art is always therefore an attempt to immortalise – writing is a way to deal with the temporal, in both senses of the word, the worldly and the time-bound. Bar-Nadav writes that her “dead father knocks on a little paper door” (Bar-Nadav 2) – he is reborn every time he is invoked on the page. We can breathe new life into those we have lost by writing about them, and doing so is a way of grieving and also of dealing with the problem of finitude. Kristeva says that to look upon the dead body of Christ is to “bring him back to life” (137) and make his death meaningful. I think what Kristeva means to say is that to paint him is to keep his suffering in view, and that there is a relationship between witnessing and remembrance. Both Holbein and Bar-Nadav, as painter and writer, reveal art as a sacred place. It is by turning grief into art that we can try to make terrible things meaningful. We are reborn through artistic production, both artist and witness, reborn every time we are forced to face our mortality in all of its monstrosity, and through art-making, through representing the terrible, we can transcend, for a short while, our own ephemerality. Kristeva asks whether art might then be understood to be a substitute for prayer (138): to this I answer yes, maybe.

Bar-Nadav’s poetry is humane and beautiful. She paints for us an unsettling picture of illness and death but writes in the end that when the heart stops it “sleeps” (Bar-Nadav 16). I am struck by the significance of this word. The writer-artist, in some sense, refuses to believe in death, and the faithful who observe Holbein’s Christ continue to believe that Christ is not dead but asleep. This is how the writer-artist performs miracles, by presenting us with things as they are, strange and bleak, but inviting us to wonder about them, about what they signify and if they might be made miraculous. We see here the existentialist impulse – to search for meaning, sometimes desperately, in the face of nonmeaning. Holbein and Bar-Nadav show us that we can expect revelation from rupture, salvation from severance – that out of meaninglessness (a)rises so much meaning. Both show us that there may not be a beyond in the divine, transcendent sense, but that there is something beyond grief that might inform one’s work and living, a grief that animates and brings to life the consolatory practice that I think art-making is.

Works Cited

Bar-Nadav, Hadara. Poems from Lullaby (with Exit Sign), 2013.

Kristeva, Julia. “Holbein’s Dead Christ.” from Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, 1989.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Selections from The Birth of Tragedy, 1872.

Biography: Veronika studies ethics, society, and law and philosophy. She has particular affections for philosophy of history and political and critical theory, and is interested primarily in questions of exile, trauma and memory, archives, and translation. When not writing she enjoys 20th century art and poetry, and Armenian studies.

By Mukti Patel

In a TV special produced in 1970 by the MGM Animation studio based on Dr. Seuss’s Horton Hears a Who, an elephant named Horton is depicted splashing near a waterfall when he hears a quiet cry for help from a speck of dust. He chases and catches the speck on his tusk, suspecting that there is a small person on it, and carefully places it on a pink clover. Jane Kangaroo sees Horton speak to the speck and castigates him, suggesting that his belief in hearing a Who is unjustified. This short encounter encapsulates a philosophical issue in debates about religious beliefs. Is Horton justified in believing that he has heard a Who? In this investigation, I examine whether Horton’s action of believing is indeed justified, which is a question distinct from whether a Who exists, namely, whether Horton’s belief is true. I will consider the ways in which extraordinary sense experiences, particularly, Horton’s hearing a Who, can justify his belief by drawing on philosophical conversations about religious belief from Europe, America, and South Asia.

I. Jane’s Attack: Never-Has-Been

When Jane the Kangaroo sees Horton place a speck of dust on a pink clover, she hops over to examine the speck of dust; with a look of disapproval, she then reprimands Horton. Jane’s response is to be expected: one need not be a skeptic to assume that there is something seriously odd about not just Horton’s experience but the belief he forms on its basis. But acknowledging this resistance to extraordinary beliefs, formed based on equally extraordinary experiences, is different from affirming that we or Jane believe that Horton’s belief is unjustified on good grounds. Jane rejects Horton’s belief because a) she has never heard of a Who, and b) she considers Horton a fool and therefore unreliable.

In denying Horton’s belief in hearing a Who, Jane Kangaroo evaluates Horton’s claim by proportioning Horton’s belief that he hears a Who to the existing evidence. This line of reasoning is found in Hume’s famous essay “Of Miracles,” where he argues that people should proportion their beliefs with evidence: this proportionality principle is useful in considering justification of evidence, and therefore, in determining whether a belief should be held. She decides that the evidence against outweighs evidence in favor, and therefore, she rejects the argument that Horton is justified in his belief.

A key reason for which Jane rejects Horton’s belief is that neither Jane has ever heard of a Who, let alone experienced one. As she peers at the pink clover with her black spectacles, Jane remarks, “A person on that? There never has been.” Let’s call this principle the ‘never-has-been’ principle (henceforth NHB). Jane is in good company in her distrust of Horton’s experience: Hume, too, attacked testimonies of miracles on the very basis Jane does. Because Jane has never known of a person on something as “small as the head of a pin,” she concludes that the speck of dust is unable to inhabit life. Hume has responded similarly to an example of another miracle: “It is no miracle that a man, seemingly in good health, should die all of a sudden, because such a kind of death, though more unusual than any other, has yet been frequently observed to happen. But it is a miracle that a dead man should come to life, because that has never been observed in any age or country.” Jane Kangaroo and Hume both assume that future experiences parallel the past. In the case of a man rising from the dead or noises from specks of dust, such an assumption seems justified. However, the future does not always resemble the past: consider the 2016 presidential election in America. Just because a business tycoon lacking political experience has never been elected president before does not mean one can never be. Therefore, Jane’s assumption that just because there has never been a person small enough to cry for help from a speck of just does not preclude the possibility of it occurring in the future.

Furthermore, Jane’s current argument prevents not just miracles, as Hume discusses, but also unexpected discoveries. Consider as a counterexample to NHB the following necessarily vague case of scientific discovery which often repeats itself in history. Up until now we affirmed Theory A when thinking about what reality is made up of. Theory A explained reality using only observable particles. As of late, new evidence was discovered and studies over time confirmed Theory B, which came to supersede Theory A. Theory B, however, explained reality using phenomena that were not observable, appealing to particles that were never before known to exist. In science, our understanding of the world constantly changes based on new discoveries. If Jane rejects Horton’s belief because it does not correspond with what is familiar to her, she may similarly be unwilling to accept that a new strain of coronavirus is extremely dangerous to the world just because she has never seen anything like it before. Such discoveries are made through faculties that Horton uses–– sense perception and inference, which are explored in more detail in section III. But because Jane rejects it on the grounds that it was not the case before, she would reject far more than miracles alone. Under certain interpretations of NHB, the principle would also not to be able to account for more straightforward scientific discoveries, such as of the Earth’s being spherical or the Sun’s being at the center of the solar system, because each of these were unprecedented discoveries in their time. NHB as Jane expressed it is not so clearly justified.

II. Jane’s Issue with Testimony

To determine if the evidence in favor of Horton’s claim is legitimate, Jane questions Horton’s testimonial evidence with attention to his nature. Rightfully so, Jane should assess the reliability of testimony as a way of knowing–– according to models in South Asian philosophy, specifically from the school of logic (Nyāya), a reliable speaker whose testimony should be regarded has specific qualities. A speaker should be competent, honest, and willing to communicate. According to Jane as she calls him a “fool,” Horton is an incompetent speaker, but she does not provide sufficient justification for such a claim.

Using Hume’s very proportionality principle, I seek to apply the same standards of justification back onto Jane, testing her belief that Horton is unreliable. According to Jane, Horton is an incompetent speaker, but does not provide concrete justification for her claim. In the film, Horton does not exhibit the foolish behavior that Jane Kangaroo claims. Jane’s evidence likely precedes the short film, as she relies on her last twelve years of knowing Horton to support her belief. She states, “Horton, I’ve known you twelve years in this jungle, and I’ve always considered you somewhat a fool.” She herself did not have the sensory experience and therefore is limited to balancing her memory and Horton’s testimony to judge Horton’s claim, so she determines that Horton’s testimony about his sensory experience is unreliable in comparison to her memory. Memory, however, can be misleading, as it is often shaped and reshaped by biases, so Jane Kangaroo’s memory of Horton’s character is a fallible justification for her belief.

Another reason to doubt Jane’s critique of Horton as a speaker is that understanding someone to be a fool is not enough to dispute the reliability of all their testimonies. There are many kinds of testimony, requiring varying levels of competence, and impugning someone’s credibility for one kind of testimony does little to do so for the other kinds. In other words, just because someone is bad at math doesn’t necessarily mean that their testimony on topics concerning history of math are unreliable. So even if we assume Jane is correct, and that Horton was somewhat foolish, it does not immediately follow that his belief in hearing a who is unreliable.

Finally, although Horton’s character—for example, whether he has a tendency to lie—would certainly matter to a judgment of the reliability of his testimony, we might unproblematically ignore this critique by considering whether, in the first place, Jane’s critique was even intending to repudiate Horton’s reliability as a speaker. After she admits to Horton that “I’ve always considered you somewhat a fool,” she follows with, “But talking to dust specks? That is really cuckoo.” Her remark seems to suggest that Horton’s interaction with the speck confirmed and exacerbated her judgment of his being a fool. In other words, she had already assumed the falsity of Horton’s belief and used such an assumption to confirm a prior judgment of Horton’s intelligence.

III. The Defense: Horton’s Epistemic Reply

Horton is convinced that he repeatedly hears small cries for help. He searches nearby for the source of the noise and traces it to a speck of dust. He reasons that there must be a person on the dust particle based on his hearing. Horton relies on his experience, which he had through sensory perceptual power, to justify his belief that he heard a Who. Arguing like a theist evidentialist, he posits that he has experiential evidence to substantiate his beliefs. Just as ordinary experiences can justify ordinary belief, a consonance between extraordinary and ordinary experiences justifies religious belief. In discussing religious beliefs, Swinburne offers the example of Jesus’s last supper to illustrate a religious belief: three days after the crucifixion, a man who looks like and talks like Jesus joins the disciples to eat fish. Thus, the disciples had the religious experience that Jesus had risen. Alston suggests that a religious experience is analogous to an ordinary perceptual event because both only require faculties found universally among human beings. Horton uses the same ears to hear Jane and the Who speak. Extraordinary experiences, much like ordinary experiences, arise from conscious perception and cause an event in the mind of the perceiver. Extraordinary sense experiences are not essentially different from ordinary sense experiences: rather, their unfamiliarity makes them seem extraordinary, but as argued above, past experiences do not prevent future occurrences. By accepting extraordinary experience as evidence on account of its commonality with ordinary experience, religious belief can be justified. In Horton’s case, his hearing justifies his belief in the Who, despite it seeming like an extraordinary belief.

Horton’s hearing justifies his belief in the Who. He says, “I tell you, sincerely, that these extra big ears of mine heard him.” In other words, Horton’s elephant ears enable him to hear softer sounds with greater acuity, particularly when contrasted with Jane’s ears. Horton and Jane experience the same event differently based on difference in sense perception, which affects their individual acceptance of the sensory experience as evidence. The evidence Horton maintains for his belief is fallible in the way that any sensorial experience is fallible; for example, his senses might be damaged, or other factors might confuse him into thinking we perceived something when in actuality we did not. In this case, Horton could have mistaken the sound of wind for a cry. However, given that no such factors have been shown to affect Horton’s hearing, Horton’s testimony is sufficient for his own belief. Are we to question, each time that we hear a voice through a cell phone, whether we truly heard it? According to the principle of credulity, if it seems that x is present, it probably is– unless we have reasons not to believe, is a reason to believe. Until provided with reason for suspicion, or more specifically, unless his ears are known to trick him, Horton has no reason to mistrust his hearing capabilities.

Directly following Horton’s perception of a sound is his inference that there is a Who. Because inference is a crucial step in how Horton knows about Whos, I am exploring the inference within discussions on epistemology. In South Asian philosophy, elements of a sound inference (anumāna) include a logical reason (probans, hetu), subject (locus, pakṣa), and conclusion (probandum, sādhya). It resembles an Aristotelian syllogism with the addition of an additional locus to verify the inference, excluding the possibility of empty sets. In this example, Horton’s probans is the cry for help, and his probandum is the presence of a who. The locus of this inference is the speck of dust, and an additional locus would be his experiences hearing cries for help coming from living beings in the forest. Horton likely has heard other animals making similar noises in the forest, and so he knew that such a sound is a cry for help from a living being. Granted that Horton heard correctly, which the principle of credulity has established, the interference stands. According to Horton, where there is a cry for help, there is a person, and an invariable concomitance (vyāpti) exists between the two. Therefore, he can safely infer the presence of a living being because he heard a yelp.

IV. Justifying Horton’s Belief: Horton’s Humanitarianism

Apart from epistemic justification for his belief, notable utilitarian justification exists for the same. Horton relies on truth-independent prudentialism, meaning regardless of whether his belief correlates with reality, he sees a material benefit in holding the belief, much like the case of Pascal’s wager. Pascal, informed by decision theory, argues that it is more rational to believe in God than not because of the utility of the belief: belief in God guarantees an elevated position in the afterlife with little to lose, but disbelief does not offer any benefits. Likewise, Horton seems to weigh that it is more pragmatic to believe in the Who rather than to deny its existence. Horton cannot know for certain whether a Who exists, but his action of believing can be justified in the immediate as having ethical utility. Without his belief in hearing a Who, the entirety of Whoville would perish.

In weighing the outcomes of the belief, there is a potential social loss that Pascal’s wager does not account for: accepting belief at the risk of projecting insanity. Should Horton help a life form possibly in anguish and risk looking insane, or should he neglect the life form for the sake of social clout? The latter is inherently selfish, but Horton’s character is evidently compassionate, as proven through his actions. Horton can gather possible truth only if he risks error. Discovering truth and avoiding error seem to be two competing intellectual imperatives but avoiding error cannot be equated to finding truth. William James writes in “The Will to Believe,” that “our passional nature… must decide an option between propositions… for to say …‘Do not decide, but leave the question open,’ is itself a passional decision,—just like deciding yes or no,—and is attended with the same risk of losing the truth”. While James suggests that we must come to a decision, his underlying assumption is that any decision entails risk. Horton’s ethical duty to save a life is dependent on accepting this belief, so he risks the error of his social reputation in the pursuit of some possible truth.

V. Final Position

For these reasons, Horton is justified in holding his belief that he hears a Who. The question at hand is not whether his belief is true, but rather, if he is justified in holding such a belief. Jane’s arguments to the contrary, regarding her own memory and Horton’s character, are epistemically erroneous and fail to problematize the trustworthiness of Horton’s testimony. Therefore, Jane has no reason to doubt Horton’s testimony, other than the mere possibility that Horton is lying or that something is wrong with his sense perception; these are always possible with testimony, but there is no evidence for either. If we presuppose the compelling principle of credulity in evidentialism, we are not justified in believing that his testimony is flawed. Horton’s reasons for believing can be taken as true until legitimate doubts are otherwise raised. Though Jane does not accept Horton’s sensory experience as evidence, Horton’s prudentialism further justifies his belief, for he is doing more good than harm in holding his belief. If he were to neglect the belief in favor of social status, then the life of a sentient being would be at risk. Therefore, the benefits of belief outweigh losses in Horton’s risk assessment.

Bibliography

Alston, William P. “Religious Experience and Religious Belief.” Noûs 16, no. 1 (1982): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.2307/2215404.

“Horton Hears A Who (1970)” video file, Youtube, posted by Lex The Bookworm, July 22, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tg4Xa0ln3sI

Hume, David. “Of Miracles,” from “An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding” in Essays, Moral, Political and Literary eds. T.H. Green and T.H. Grose, London: Longmans, Green, 1889.

James, William. The Will to Believe, and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. Project Gutenberg, 2008.

Pascal, Blaise. Pensées. Translated by W. F. Trotter. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1931.

Stephen H Phillips. Epistemology in Classical India: The Knowledge Sources of the Nyaya School. Taylor and Francis, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203152386.

Speer, Megan E, Sandra Ibrahim, Daniela Schiller, and Mauricio R Delgado. “Finding Positive Meaning in Memories of Negative Events Adaptively Updates Memory.” Nature Communications 12, no. 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26906-4.

Swinburne, Richard. “The Argument from Religious Experience.” In The Existence of God. 2nd Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Scholarship Online, 2007. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199271672.003.0014.

Biography: Mukti Patel is a fourth-year student specializing in religion and minoring in writing and rhetoric at the University of Toronto. She is broadly interested in religion in South Asia with attention to philosophy, literature, and history. In fall of 2022, Mukti will join the MA program at the University of Chicago to further her study of religion.

By Qizhou Cui

Abstract

In his paper Transparent Pictures: On the Nature of Photographic Realism, Kendall Walton observes that photographs and hand-made drawings (e.g., paintings, sketches, etchings, etc.) affect us very differently. Specifically, we seem to experience a sense of intimacy and contact with the objects of photographs that is less pronounced when viewing those objects in a drawing. Walton’s explanation of this phenomenon is that photographs are ‘transparent’ while drawings are not. In this essay, I will offer an alternate explanation for this phenomenon. I argue that we feel a stronger sense of contact with the objects of photographs because we believe that, in general, photographs are more epistemically reliable.

I. Introduction

In his paper Transparent Pictures: On the Nature of Photographic Realism, Kendall Walton highlights an important phenomenological difference between our experiences before photographs and hand-made drawings (e.g., paintings, sketches, etchings, etc.). Characterizing this phenomenology is no easy task, but an intuitive thought is that seeing an object in a photograph feels more like being in actual, face-to-face perceptual contact with that object than does seeing that object in a drawing. Phenomenologically, seeing a photograph of Trudeau feels a lot like seeing Trudeau ‘in the flesh’, while seeing a painting of Trudeau does not. I take it that this phenomenology is what Walton has mind when he writes that:

Photographic pornography is more potent than the painted variety. Published photographs of disaster victims or the private lives of public figures understandably provoke charges of invasion of privacy; similar complaints against the publication of drawings or paintings have less credibility. I expect that most of us will acknowledge that, in general, photographs and paintings (and comparable nonphotographic pictures) affect us very differently. It’s hard to resist describing this difference in saying that [our experiences of] photographs have a kind of intimacy and realism which etchings lack.

Walton’s explanation for this phenomenological difference is that photographs are transparent while drawings are not. We ‘see through’ photographs at the objects they depict, but we do not see through drawings. Hence, our subjective experience of viewing these kinds of pictures feels different. In this essay, I will give another explanation for this phenomenological difference. I argue that the phenomenology of contact is stronger when viewing photographs because we believe that, in general, photographs are more epistemically reliable than drawings are.

In the next section, I will explain Walton’s photographic transparency thesis and how he uses it to explain phenomenological differences between viewing photographs and drawings. §III presents two problems with Walton’s explanation. In §IV-V, I present my own explanation of the phenomenological difference and give three considerations in favour of my view. In §VI, I end with some closing remarks.

II. Walton’s on Photographic Transparency

According to Walton, photographs are transparent—we “see through” them at the objects they depict. In his original phrasing: “we see, quite literally, our dead relatives themselves when we look at photographs of them.” To see a photograph of Trudeau, for instance, is, quite literally, to see Trudeau. Of course, it is not seeing Trudeau directly. One sees him by seeing the photograph of him, whereas to see Trudeau directly is to see him without the mediation of any other visible object. But nonetheless, seeing the photo of Trudeau is still a way to see him. Photographs are therefore like mirrors, eyeglasses, and telescopes; they are aids to vision. They extend the range of what we can see—in this case, all the way to someone now dead and gone. Hand-made drawings, on the other hand, are not transparent according to Walton.5 When one sees a sketch or a painting of Trudeau for instance, she does not literally see Trudeau. For Walton, the special sense of contact that we feel with the objects of photographs is the product of an actual perceptual contact, one which is lacking in our visual experiences of drawings. Hence, the difference in phenomenology.

Why does Walton insist that photographs are transparent? He seems to argue for this in two different directions. First, he believes that there are significant similarities between the way that photographs provide visual experiences and the way that ordinary vision provides visual experiences. Suppose that we see some object O face-to-face. Our ordinary vision functions in a way such that if O had been different in terms of some visual feature, this difference would be reflected in our visual experiences. Similarly with photographic images, they are counterfactually dependent on the scenes they represent. For example, had Trudeau been frowning at the camera rather than smiling, the resulting photograph of him would have looked different.

Moreover, when it comes to ordinary face-to-face seeing, this counterfactual dependence is not mediated by the mental states of other agents. The external world causes me to have visual experiences in a way that does not involve what others believe, desire, etc.

Crucially, this feature of ordinary vision is present when viewing photographs, but not when viewing drawings. When the photographer clicks the camera shutter, the camera’s physical mechanisms take over and the image is formed without any further involvement of the photographer. Drawings, by contrast, involve the artist’s mental states throughout the formative process. Not only does he decide what to paint and when to paint it, but once these decisions are made, he must continue to make many decisions about the arrangement of marks that constitute the image. Had the artist believed something different about the scene being drawn, then my visual experiences would be different too. This is one reason why Walton thinks that photographs are transparent while drawings are not.

According to the second line of reasoning, the transparency thesis gains support from its explanatory capacity. Here is how Walton puts it in a reply to one of his critics: “[Transparency] seems more inevitable than incredible, on reflection, however startling it might be at first. It is reinforced, moreover, by the contribution it makes to an explanation of the peculiar powers of photography…. If we deny the transparency of photographs, we will still be groping for explanations.” One of “the peculiar powers of photography” is precisely its phenomenological power.

III. Problems with Walton’s Account

I have just explained how Walton appeals to a difference in transparency to explain the phenomenological difference between seeing photographs and hand-made pictures. I am not convinced by Walton’s view, and I will now state what I think are two problems with his explanation.

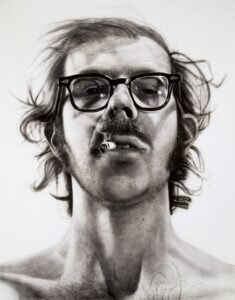

The first is this. It is often said that we experience a ‘jolting effect’ once we discover that what we previously took to be a photograph is actually a hyper-realistic drawing. Walton says this about a hyper realistic self-portrait by artist Chuck Close (figure 1):

[Our discovery] jolts us. Our experience of the picture and our attitude toward it undergo a profound transformation, one which is much deeper and more significant than the change which occurs when we discover that what we first took to be an etching, for example, is actually a pen-and-ink drawing. It is more like discovering a guard in a wax museum to be just another wax figure. We feel somehow less in contact with Close.

Walton uses this example to dispel the intuitive thought that we feel more closely in contact with photographic depictions simply because they look more like ‘the real thing’ than pictures of the drawn variety. On this line of reasoning, photographs possess a kind of detail that drawings lack, and this is what brings about that special sense of contact. According to Walton, our initial experience of Close’s self-portrait feels just like a photograph-induced visual experience. However, after the ‘jolt’, this quickly collapses into a less intimate drawing-induced experience even though the portrait is just as detailed as it was before. This suggests that the special sense of contact associated with seeing photographs cannot be a matter of how detailed the picture looks.

Figure 1. Chuck Close, Self-Portrait, acrylic on canvas, 1968. Collection Art Center, Minneapolis. Art Center

I agree with Walton on this point, but it seems to me that his own account cannot make sense of this phenomenon either. Recall that for Walton, the special sense of contact that we feel with the objects of photographs is a product of an actual perceptual contact, one which is lacking in our visual experiences of handmade pictures. But this can provide no explanation for why, at first, one feels this special sense of contact with Chuck Close. For it is a painting one sees. Paintings are non-transparent on Walton’s account. So, by Walton’s own lights, it is not true that one is actually seeing Close. To the extent that Walton explains photographic phenomenology solely in terms of transparency, we have no explanation for how the phenomenology typical of seeing objects in photographs managed to occur in the case of seeing an object, i.e. Close, in a hand-made drawing. What this case shows is that an actual perceptual contact is not necessary for a feeling of contact at all. This spells trouble for Walton.

Here is the second problem with Walton’s account. His explanation for why photographs and hand-made pictures affect us differently presupposes that photographs (unlike drawings) really are transparent—i.e., that we actually see the depicted object. But there are reasons to doubt this. In their paper On the Epistemic Value of Photographs, Cohen and Meskin propose a necessary condition for a subject S to see some object O: S’s visual experience must ‘carry egocentric spatial information’ about O’s location. The idea here is that S’s experience needs to represent where O is located spatially in relation to S. When it comes to ordinary vision, this condition of seeing is met. When I see a building in my peripheral vision, my experience represents the building as being at a particular location relative to me (e.g., to my right). Prosthetic seeing like the type involving telescopes, eye-glasses, etc. also satisfies this condition.15 When I use my telescope to see Neptune, for instance, my visual experience represents where Neptune is located relative to my current position.

But what about photographs? When I look at a photo of the Eiffel Tower, my visual experience does not represent where the Eiffel tower is relative to my location. When I walk around with the photo, the Eiffel Tower’s relative location to myself will change but this change will not be represented to me by looking at the photograph. If Cohen and Meskin’s condition for seeing is correct, then photographs are not transparent. Walton’s thesis about photographic transparency is very controversial, and insofar as he needs to appeal to this thesis to explain the special affective capacity of photographs, this is a problem.

Let’s take stock. I started by giving Walton’s explanation of why, relative to drawings, our experiences of viewing photographs feel more like ordinary, face-to-face seeing. And next, I raised some problems with his account. In what follows, I will present my own explanation for this phenomenological difference.

IV. Towards a Doxastic Solution

Unlike Walton, my own account will not reference any facts about photographs themselves to explain this difference in phenomenology. Instead, I argue that it’s the viewers’ beliefs that are explanatory.

One belief that most of us hold about ordinary vision is that it is epistemically reliable: the information we receive from this process has a high probability of being accurate. When a stranger appears in the corner of my eye, chances are there really is a person there. While we can all think of cases where ordinary vision can fail to be veridical, such as when we encounter optical illusions, we all know that these cases are quite uncommon in our everyday lives. We know that in general, our ordinary vision gets the facts right.

I suggest that we also believe that photographs are epistemically reliable in this sense.

It’s for this reason that we use photographs as evidence, in both formal and informal contexts. The use of photographs as evidence goes back to the very earliest days of photography, such as when they were used as legal evidence in trials during the American Civil War. Today, photographs can act as evidence in newspapers, blackmail plots, courts of law, etc. Photographs also serve in informal contexts as evidence about all sorts of things, such as what we and our loved ones looked like in the past.

But now let’s consider hand-made drawings. Most of us do not think that drawings alone suffice to constitute evidence. We do not respond to the question ‘Why do you believe that?’ with ‘Well, I saw it in a painting’. At least, not without some further comment about who made it, where it was displayed, and so on. The presence of higher-order evidence is very important for whether we take drawings as evidence, while it is less important for whether we take photographs as evidence. Hence, drawings are rarely used as evidence in newspapers, blackmail plots, or courts of law, etc. For this reason, I suggest that most of us think that in general, photographs are epistemically more reliable than drawings are.

On my view, the more confident we are that a visual representation is epistemically reliable, the more in-contact we feel with their contents. When it comes to ordinary vision and viewing photographs, we are usually very confident that the information we are being presented with is accurate. Hence, we feel a sense of contact with the objects of photographs that’s similar to the kind found in ordinary vision. But since we tend to take hand-made artworks to be less epistemically reliable, that feeling of contact is less pronounced.

V. Considerations in Favour

Why should one think this is a good account of the distinct phenomenology of viewing photographs? I believe there are at least three considerations in its favour.

First, my account can explain puzzling features of our experiences before hyper-realistic drawings. This is because my account treats the phenomenology of contact as contingent upon the psychological states of the viewer, rather than as a product of the medium itself (as Walton contends). So what exactly does my account say about the jolt? In the initial stage of our experience, where we believe ourselves to be seeing a photograph, we are very confident that the information presented to us is true, since we know that photographs are generally reliable at telling the truth. Our mental states could be illustrated as:

- Photographs are epistemically very reliable, generally speaking

- I am seeing a photograph

- Therefore, the information being presented is probably accurate

Upon realizing the picture is a hand-made one, our attitude shifts. Recognizing the picture to be hand-made, we are more guarded because we know that on average drawings are worse than photographs at getting the facts right. Where before we believed Close to look how our visual experience represented him to be, we are now less certain. We see the cigarette, horn-rimmed glasses, wild hair, and so on, but we don’t know how accurate the depiction is. We might even take ourselves to require more evidence before believing the information this is presented to us. For instance, evidence about how Close looks in reality, his goals for producing the picture, etc. Hence, Close seems more distant somehow, less present to us, upon the realization it is a painting we are looking at.

The second consideration is this. My account remains neutral on the issue of whether photographs, unlike drawings, really are transparent. There is ongoing debate surrounding this claim, and unlike Walton’s account, mine need not presuppose any controversial theses about the nature of the photographs themselves. On my view, whether or not photographs are transparent is irrelevant with respect to the viewer’s felt sense of contact. What is important, I suggest, is simply the viewer’s psychological attitudes.

The last consideration is that my account explains why the phenomenology of contact comes in degrees. For one, my account is able to explain why we feel a stronger degree of contact when we see a photograph of Churchill than when we see a painting of him. We believe that in general, photographs are epistemically more reliable than paintings are, so the phenomenology of contact is stronger in the former. But my account would not be special if that is all it was able to explain, for Walton also tells us why we feel more in contact with the objects of photographs. Where my account is superior is this: I am able to explain why even within the categories of photographs and hand-made pictures, the amount of contact we feel is not uniform but comes in degrees.

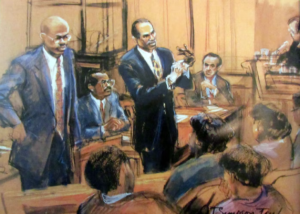

There are certain “traditions” of art which are known by and large to be epistemically reliable (and therefore commonly used as evidence). Some examples include courtroom sketches, royal portraitures, anatomical sketches, etc. Our experiences suggest that we feel particularly in contact with what these drawings depict, more so in comparison with other drawings. Take, for instance, the famous courtroom sketch from OJ Simpson’s trial (figure 2). Here, we feel a strong sense of intimacy and contact with OJ and his trial that is quite uncommon among most drawings that we see. My account is able to explain why this is. We know that in many jurisdictions, cameras are not allowed in courtrooms in order to prevent distractions and preserve privacy. And because of this, the artists who produce these sketches are credible members of the media who intend their work to be an accurate depiction of the events that take place. Unlike most drawings we come across, we believe that the information presented to us is likely accurate. Hence, the special sense of contact.

We feel varying degrees of contact when we view hand-made drawings. But what about photographs? Suppose that you come across an object in a photograph but simply fail to realize you are seeing a photograph. For example, you might believe that you are seeing a sketch or a painting, say. You might even wrongly assume that you are seeing a ‘photoshopped’, composite image. Still, you are seeing a photograph, but it’s doubtful that your experience will feel very much like it. Phenomenologically, you will feel more intimacy and contact when you view photographs from newspapers, bus advertisements, your friend’s Instagram posts, etc. On my view, this is because you’re more confident about the information you receive from photographs than the information you receive from drawings.

Figure 2. O. J. Simpson Trial, 1995. Marilyn Church

While my account explains why we experience various degrees of phenomenological contact both when we view photographs and hand-drawn pictures; Walton’s account does not. According to Walton, we feel more contact with the objects of photographs by virtue of a perceptual contact that we lack with the objects of hand-made images. But by referencing transparency, there’s no room in his account for explaining why we feel more contact with certain non-transparent pictures than others, or why we feel more contact with certain transparent pictures than others. Walton can only tell us why photographs affect us more than hand-made pictures.

VI. Closing Remarks

An interesting question that one may ask is why viewers believe that photographs are epistemically more reliable than drawings. One possible reason is that most of us know that cameras are designed to produce pictures that accurately depict the scene being captured. But on the other hand, we know that not all drawings are intended to be accurate depictions of the world. We know that for many artists, various aesthetic considerations factor into how their drawings look. This might be why we think that they are less reliable than photographs are. Another possible reason is this. Everyday experience suggests that photographic representations of the world generally are very accurate. When one takes a photograph, they typically turn out looking like the scene being captured. But this is not true of the drawings we see; they tend to look different from the real thing. And on the basis of these experiences, we generalize that photographs are epistemically more reliable.

In this paper, I investigated the question of why we find ourselves feeling more in-contact with the objects of photographs than the objects of drawings. First, I presented Walton’s explanation that photographs are transparent while drawings are not, and I showed why this explanation is inadequate. Next, I offered my own explanation and gave several considerations in favour of it. On my view, phenomenology of contact is stronger when viewing photographs because we believe that in general, photographs are more epistemically reliable than drawings are.

References

Church, Marilyn, and Michelle Legro. “The Courtroom Artist Who Sketched Trump on Trial.” Topic. May 06, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://www.topic.com/murder-shedrew.

Cohen, Jonathan, and Aaron Meskin. “On the Epistemic Value of Photographs.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 62, no. 2 (2004): 197-210. doi:10.1111/j.1540-594x.2004.00152.x.

Cohen, Jonathan, and Aaron Meskin. “Photographs as Evidence.” Photography and Philosophy, 2008, 70-90. doi:10.1002/9780470696651.ch3.

Dretske, Fred I. “Simple Seeing.” Body, Mind, and Method, 1979, 1-15. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-9479-9_1.

Walton, Kendall L. “Looking Again through Photographs: A Response to Edwin Martin.” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 4 (July & Aug. 1986): 801-08. doi:10.1086/448368.

Walton, Kendall L. “Transparent Pictures: On the Nature of Photographic Realism.” Critical Inquiry 11, no. 2 (1984): 246-77. doi:10.1086/448287.

By Owen Huisman

Abstract

In Works of Love, Søren Kierkegaard divides love into two types: Christian love of the neighbour and poetic love (Kierkegaard 46, 50, 52). Love of the neighbour is non-preferential love directed towards all human beings, whereas poetic love is directed towards a particular beloved (Kierkegaard 46, 48, 52). Kierkegaard assigns to Christian and poetic love the qualities of eternity and temporality respectively, with these qualities mandating distinct ways of enacting these forms of love (Kierkegaard 46, 48). Kierkegaard emphasizes that Christian love necessitates immediate action, specifically action which results in the ‘conversion’ of others, meaning the awakening of others to an awareness of the ethical necessity of universal love (Kierkegaard 46, 48). Kierkegaard characterises poetry as inherently reflective, with this reflective quality rendering the creation of poetry an inadequate response to Christian love’s call for immediate action (Kierkegaard 46, 48). In this paper I argue that T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets disrupts Kierkegaard’s assumptions that poetry is an inadequate response to Christian love and that truly ‘Christian’ poetry is an impossibility. To do so, I begin by demonstrating the similarities between Eliot’s descriptions of eternal love and Christian love. I argue that the Four Quartets accomplishes the ‘conversion’ of the reader to universal love through a disruption of the reader’s attachment to temporal love. Together with this demonstration of the ‘Christian’ content of the poem, I show that Eliot’s use of reflection to produce the ‘conversion’ of the reader challenges Kierkegaard’s dichotomy between direct and reflective responses to Christian love.

Introduction

In Works of Love Søren Kierkegaard questions the possibility of Christian poetry, based on the connection between poetry and the preferential love of particular individuals as opposed to the Christian love of the neighbour (Kierkegaard 46, 50, 52). Kierkegaard proposes that the realization of Christian love involves recognizing the needs of the neighbour and acting to fulfill these needs, whereas poetry’s necessarily reflective character bars it from being a successful response to the needs of the neighbour (Kierkegaard 46, 48). However, T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets challenges Kierkegaard’s proposal that poetry cannot contribute to the realization of Christian love, because the Quartets serve to disrupt the reader’s attachment to preferential love. The Quartets accomplish this disruption by alerting the reader to the temporality of preferential love and the despair that both Kierkegaard and Eliot associate with this temporality (Eliot “Burnt Norton” V.26-31, Eliot “Little Gidding” III.8-11, Kierkegaard 65-67). Furthermore, Eliot’s close attention to the temporality of language, as well as the shared nature of memory, proves that the Quartets are ‘direct’, which Kierkegaard requires expressions of Christianity to be, while also elucidating what ‘directness’ must mean in relation to eternal love. Thus, Four Quartets demonstrates the possibility of poetry which responds to Christian love’s call to be accomplished, while also expanding upon what is required of any attempt to speak or write directly about eternal love.

Christian and Preferential Love in Works of Love

Kierkegaard’s critique of poets develops out of his dichotomy between Christian love and preferential love. Preferential love is the form of love which one typically feels for a friend, family member, or romantic partner (Kierkegaard 44, 52, 56). Kierkegaard contends that this form of love leads an individual to act with a preference for their loved one, which supersedes one’s general ethical duties towards all persons regardless of their identity (Kierkegaard 45, 49). This indicates that one who engages in preferential love treats their own preference as the most important principle when determining how to act (Kierkegaard 45, 49, 53-54). Preferential love is dependent upon both the lover and the beloved maintaining a certain degree of consistency. Given the ever-present potential for the beloved to change, either through an alteration of the beloved’s character, through a change in the beloved’s orientation towards the lover, or because the beloved dies, such consistency can never be certain (Kierkegaard 65-67). Furthermore, if one’s love for a beloved ends, then despair occurs (Kierkegaard 65-67). Thus, preferential love always exists within a limited period—that is, at it’s longest it lasts until the beloved dies, but may end even earlier if the beloved changes—and always exists as a possibility-of-despair (Kierkegaard 65-67).

Given that preferential love for someone justifies itself as a guide for action only for the individual whose preference it is founded upon, any expression of preferential love does not indicate that the listener should take the speaker’s particular preferences as a guide for their own actions (Kierkegaard 58-59). Thus, written or spoken expressions of preferential love do not produce any conflict within the listener regarding which principles/loves should determine how one ought to act (Kierkegaard 58-59). Kierkegaard sees poets as typically praising a particular beloved (Kierkegaard 89). While such praise does not necessarily lead the listener to love the poet’s beloved, it does elevate the prestige of preferential love for the listener (Kierkegaard 89). Given this connection, Kierkegaard uses ‘preferential love’ and ‘poetic love’ interchangeably.

Christian love, unlike poetic love, is not the love of a particular beloved, but is love of the neighbour, meaning the love of every person by virtue of them being a person (Kierkegaard 89). Christian love rejects personal preference as a suitable justification for revealing who ought to be loved (and thus, who should be treated ethically), instead taking up the Biblical commandment to love the neighbour as the proper principle for discovering who should be encountered as a loved one (Kierkegaard 89-90). Kierkegaard considers such commandments to be eternal truths revealed by God (Kierkegaard 89-90). Christian love’s object, the neighbour, is any-and-every-person, and while individual neighbours may change or die, Christian love cannot lose its object insofar as any person still exists (Kierkegaard 65). Given its eternal basis (God’s command) and always present object (the neighbour), Christian love is itself eternal and unchanging, and thus is not a possibility-for-despair. Unlike preferential love’s validity for the singular lover, Christian love—being a divine commandment—asserts itself as a universally applicable and primary principle for determining how to act (Kierkegaard 58). Thus, expressions of Christian love should unsettle a listener who engages in preferential love, as the listener is called to acknowledge that only the commandment to love the neighbour should structure their own loves (Kierkegaard 58). This conversion of the listener—meaning, the unsettling of preferential love and its replacement with Christian love—is thus the task of any expression of Christian love. This conversion of the listener is beneficial for the listener by providing them with knowledge of ethics and by removing from the listener any possibility of despair by changing the particular beloved into the neighbour, who—as ‘any person’—is never absent, dead, or changing.

Kierkegaard’s Rejection of Poetry as a Proper Expression of Christian Love

Kierkegaard’s rejection of the possibility, or at least the relevancy, of the Christian poet is reliant upon a connection between poetry as a specific mode of communication and preferential love. As discussed above, poetic expressions of love typically refer to a particular beloved and thereby lead listeners to become more entrenched in their own preferential loves (Kierkegaard 89). Even when the poet chooses to write about Christian topics, Kierkegaard remains skeptical that the poet can “help others (in such a way as one person can help another, since God is the true helper) to become Christians in an even deeper sense”, that is, realize that they too are commanded to love the neighbour (Kierkegaard 48). Kierkegaard bases this skepticism on the principle that “Love of the neighbour does not want to be sung about — it wants to be accomplished” (Kierkegaard 46). What Kierkegaard means here is that while Christian love constantly presents one with future tasks to complete—such as dethroning one’s preferential ways of loving, or in assisting the neighbour—poetry or ‘singing’ is reflective, as the poet draws upon their own past or present experiences of love (Kierkegaard 46, 48). Were the poet to attempt to reflect upon Christian love such that they may ‘sing’ about it, they would discover a “disturbing notice” that they must instead “Go and do likewise”, as Christian love demands its continual enactment insofar as any neighbour (anyone) is suffering (Kierkegaard 46, 48). Thus, Kierkegaard thinks that insofar as poetry fails to improve the condition of the neighbour, it must be considered an insufficient way of enacting Christian love.

Love and Conversion in the Four Quartets

In the Four Quartets, T.S. Eliot disrupts Kierkegaard’s binary division of love by reflecting on love without reference to any beloved, neither a particular loved one nor the neighbour (Eliot “Burnt Norton” V.26-31, Eliot “Little Gidding” III.8-11). However, the love which Eliot reflects upon—hereafter referred to as Eliotic love—shares enough similarities with Christian love that the poem should be considered as an attempt to help the reader to become “[Christian] in an even deeper sense” (Kierkegaard 48). A key feature of both Eliotic love and Christian love is that they are both eternal (in origin and persistence) yet must be expressed in and through the temporal. In Works this is expressed through the eternal origin of Christian love in the commandant, its eternal persistence through the continual presence of the neighbour, and its temporal expression both in speech about love and in responses to the presence of individual neighbours (Kierkegaard 65, 89). In Quartets the clearest expression of this is when Eliot writes that while love is unchanging and timeless, it is “the cause and end of movement” — love both motivates temporal action and is the goal of temporal action (Eliot “Burnt Norton” V.26-31). That both Christian and Eliotic love are expressed in the temporal through action/speech and can be cultivated by action/speech is necessary for a comparison of the mechanics and process of conversion through the temporal.

Eliot clearly describes this process of conversion and emphasizes its necessity—meaning he calls for the reader’s internal conversion to love as Kierkegaard does—in the penultimate canto of “Little Ginning”. This canto begins with the entrance of the dove, the Holy Spirit, which initiates a reflection on the necessity of Eliotic or eternal love as opposed to temporal, preferential desire (Eliot “Little Ginning IV.1-7). This divine origin of Eliotic love mirrors the origin of Christian love in the commandment rather than human decision. Eliot then writes that we all have a choice between two fires, both arising from love (Eliot “Little Ginning” IV.7-10). The first fire can be identified with desire or preferential love, which causes one to suffer through its necessary ending, a result of its temporality and existence as possibility-of-despair. The second fire which ‘redeems’ one from the first may be identified as Eliotic/eternal love (Eliot “Little Ginning” IV.7). This love produces suffering in the same manner as Christian love, as it causes one to become unsettled and outraged at the possibility that one has to recognize that one’s habitual temporal love is not the highest form of love (Eliot “Little Ginning” IV.7, Kierkegaard 58). While Eliotic love cannot be identified completely with Christian love, given the absence of the neighbour, this similarity between the two in terms of the relationship between temporality and the process (and source) of conversion initially demonstrates the seeming possibility of Christian content in poetry.

Four Quartets and the Enactment of Christian Love

The Quartets may thus be considered to contain Christian content, or at least criticism of preferential love for reasons similar to Kierkegaard’s, but it is only through the unique application of the reflective character of poetry that Eliot has the Quartets become truly ‘Christian’. Kierkegaard takes it as required that any writing which seeks to be Christian must move beyond pure reflection and properly respond to the call to ‘go and do’ (Kierkegaard 46). Writings, such as Works — which takes on sermonic qualities, such as directly addressing the listener or making clear statements about the nature of the commandment — count as ‘doing’ (Kierkegaard 46, 89-90). This is because of these works’ active striving to awaken awareness of the commandant in the listener and provoke a rupture with the listener’s past ways of loving (Kierkegaard 46, 89-90). That the poem, as Kierkegaard construes it, has a necessarily reflective nature means that the adoption of such future-facing aspects of the sermon in poetry is impossible. Put otherwise, ‘singing’ is always a reflection about some thing (even a thing like Christian love), whereas doing is always in response to the presence of one to whom we say ‘you’ (the listener, the neighbour, God who gives us the commandment). However, Eliot transcends the singing-doing binary by demonstrating how through an unsettling of/engagement with memory, the reflectivity of singing can function to accomplish the same conversion of the listener as the ‘doing’ of the sermon.

Memory and Conversion in the Four Quartets

The use of memory in facilitating the conversion of the listener is evidenced by Eliot’s treatment of the topic of memory itself, and also by his application of memory in unsettling the reader’s attachment to preferential/temporal love. This latter application is best reflected in the initial portion of “Burnt Norton”, where Eliot speaks of the poem’s effect upon the reader—this is the only moment in the first quartet where Eliot directly addresses the reader:

… My words echo

Thus, in your mind.

But to what purpose

Disturbing the dust on a bowl of rose-leaves

I do not know. (Eliot “Burnt Norton” I.14-18)

The poem, as we move through Eliot’s own memory, provokes the same process of remembering in the reader, thereby “disturbing the dust”, the dust which has settled on the reader’s own memories (Eliot “Burnt Norton” I.17). Thus, as Eliot moves away from his own preferential love and towards Eliotic love throughout the poem, the reader who allows for the re-examination or refreshment of their own memories may follow the same process. Memory functioning as a tool of conversion is most clearly expressed in “Little Gidding”:

The live and the dead nettle. This is the use of memory:

For liberation—not less of love but expanding

Of love beyond desire, and so liberation

From the future as well as the past. (Eliot “Little Gidding III.8-11)

Through the act of remembering, the temporality of one’s various preferential loves/desires is revealed, thereby calling upon the reader to be liberated “From the future as well as the past” —from both past misery as the result of lost love and arguably from any possibility-of-despair (Eliot “Little Gidding III.10-11). This liberation entails the expansion of love beyond the temporal. That Eliot can, or at least seeks to, provoke an unsettling of preferential love in the reader—a critical step in conversion—demonstrates the possibility of the poem as a response to the ‘go and do’. In addition, since Eliot establishes in the passage from “Burnt Norton” that the act of remembering in the Quartets is both his own and the reader’s, the ‘singing’ about particular memories is always an address to the reader about the reader, thereby disrupting Kierkegaard’s binary division between descriptive/reflective singing and responsive/active doing. Yet, an apparent paradox must be addressed: namely, that it is through various temporal experiences of memory that the eternal—love beyond desire—becomes known to the reader (and to Eliot).

That there can be ‘Christian’ poetry is reliant upon such poetry not merely being ‘Christian’ in content or converting the reader in response to the call to ‘go and do’, but upon such poetry being a direct way of responding to the call to ‘go and do’. The use of “riddles” or ambiguity by poets obfuscates Christian love (Kierkegaard 50-51). Yet the Quartets avoids both potential forms of indirectness and thereby proves that poetry can be considered a ‘direct’ way of speaking of Christian love.

Four Quartets contains a response to the critique of ambiguous or ‘ridding’ ways of speaking of love through its analysis of the temporality of language, which in turn illuminates what directness necessarily means in relation to speech or writing about eternal love. Poetry as a literary form—as well as the nature of language itself—disrupts the idea that the efficacy of an expression of Christianity is reliant upon a sort of prosaic directness or perfect description of the nature of Christian love. This is expressed in “Burnt Norton”:

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence. Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach

The stillness as a Chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness. (Eliot “Burnt Norton” V.1-7)

Eliot here highlights that language is necessarily temporal, even when it describes the divine or eternal. If language “dies”, then any attempt to speak of the eternal must attempt to present what is atemporal in a temporal medium. Thus, Eliot’s references to eternal matters in the Quartets cannot be thought of as an attempt to provide the reader with direct access to the eternal (Eliot “Burnt Norton” V.1-3). Kierkegaard agrees with Eliot on the impossibility of temporal language perfectly expressing the eternal (Kierkegaard 209). This is demonstrated when Kierkegaard describes speech about the eternal as necessarily metaphorical, since we learn speech from our temporal experience before we become aware of the eternal (Kierkegaard 209). Thus, directness cannot just be ‘preciseness’ in providing a descriptive account of the commandment to love/Christian love. For if this were the case, then Christianity would never be perfectly direct, since a completely precise account of the eternal is impossible given language’s temporality. In other words, ambiguity is endemic to language as such, not just poetry.

This passage from “Burnt Norton” also includes a positive picture of what directness must mean in relation to eternal love. While language is unable to directly express or make present the eternal, the effects of the pattern or motion of language persist “Into the silence” — that is, they persist after speech, or the reading of a piece of writing (Eliot “Burnt Norton V.1-4). In the Quartets the wider pattern or form includes the conversion of the reader. Therefore, for the Quartets—and by extension all attempts to respond to the ‘go and do’—to be considered successful, they must induce a transformation in the listener/reader which persists outside of the work or speech itself. ‘Directness’ in any discourse on eternal love must thus be considered success in impacting the listener/reader by addressing them and making them aware of the commandment to love, in such a way that persists beyond the experience of the discourse itself. Since Eliot accomplishes this conversion through Quartets, this work, and poetry, as well as any work which is not primarily descriptive or prosaically prescriptive, cannot be rejected as an invalid way of speaking directly about Christianity if that rejection is levied simply on the grounds that it is a work of poetry, or another discourse of the relevant type.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Eliot, by his discussion of memory, demonstrates to the reader the temporality of preferential love, and the suffering which comes about because of this temporality. In alerting the reader to this temporality, Eliot converts the reader by unsettling their attachment to preferential love. This conversion of the reader represents a response to the call to ‘go and do’ that confronts the poet who seeks to write about Christian love. While Eliotic love and Christian love are not synonymous given the former’s lack of concern with the neighbour, both are eternal and originate from God. The similarity of the two types of love, as well as the use of memory in the conversion of the reader makes possible an analysis of the ‘directness’ of memory and poetry as ways of talking about eternal love. Eliot’s treatment of temporality and language highlights the impossibility of a perfect description of eternal love in temporal language, which in turn, implies that directness must instead be considered the efficacy of a work in converting the reader/listener. This direct conversion is precisely what the Quartets accomplishes, and thus Eliot demonstrates that reflective forms of discourse such as poetry can properly communicate the necessity of following the commandment to love.

Biography: Owen Huisman is a third-year student specializing in religion and minoring in philosophy. Broadly interested in the history of the relationship between philosophy and religion in the English and German speaking world(s) in the 19th and 20th centuries, Owen’s recent areas of focus include hermeneutics and the religious reception(s) of German idealism.